Scapular wall slides are one of the best exercises to improve posture and build shoulder strength. They strengthen the upper back, enhance scapular mobility, and counteract rounded shoulders caused by poor desk posture.

This exercise requires no equipment, just a wall, making it accessible for beginners and athletes alike. Learning scapular wall slides is important because proper scapular movement supports healthy shoulders, reduces pain, and improves overhead lifting performance. In this guide, we’ll cover benefits, technique, variations, research insights, and FAQs.

What Are Scapular Wall Slides?

Scapular wall slides are a mobility and strengthening drill where you press your forearms against a wall and slide them upward and downward while maintaining contact.

- Primary muscles: Serratus anterior, lower trapezius, rhomboids

- Secondary muscles: Deltoids, rotator cuff, core stabilizers

This simple drill retrains scapular upward rotation and retraction—essential for pain-free overhead movements like presses, pull-ups, and snatches.

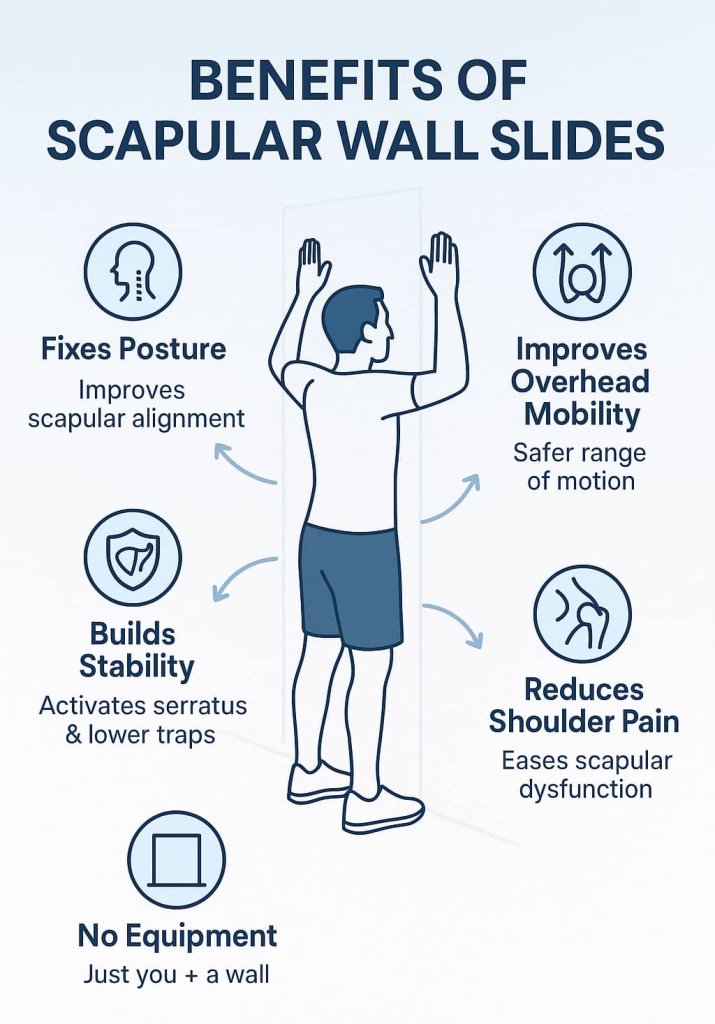

Benefits of Scapular Wall Slides

- Fixes posture: Research published in the Journal of Physical Therapy Science (2016) found that wall slides improved scapular alignment and reduced rounded shoulders in just four weeks. This makes them excellent for desk workers and students.

- Builds stability: Emphasizes serratus anterior and lower traps, balancing overactive upper traps to reduce impingement risk.

- Improves overhead mobility: Teaches controlled upward rotation for safer range of motion.

- Can reduce shoulder pain: Research shows increased pressure pain thresholds and symptom relief in scapular dysfunction.

- No equipment: Quick warm-up, posture break, or rehab add-on—just a wall.

How to Do Scapular Wall Slides (Step-by-Step)

- Set up: Stand with your back on a wall, feet 6–12 inches forward. Keep head, mid-back, and glutes touching the wall.

- Arm position: Bend elbows to 90°; forearms and the backs of hands touch the wall (a “W” goalpost).

- Brace: Gently flatten your lower back to avoid arching.

- Slide up: Glide arms toward a “Y,” maintaining light contact and avoiding shrugging.

- Return: Lower with control to the start.

- Programming: 2–3 sets of 8–12 reps, 3–4 days per week.

Trainer Tip: Move the shoulder blades, not just the arms—think “glide & rotate” rather than “shrug.”

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Arching the lower back to compensate for mobility.

- Shrugging shoulders instead of engaging lower traps.

- Losing contact with the wall (elbows or wrists lifting off).

- Rushing the movement instead of controlling scapular motion.

Variations of Scapular Wall Slides

1. W/Y Wall Slides

In this variation, you alternate between the “W” position (elbows bent at 90°, tucked closer to your sides) and the “Y” position (arms extended overhead in a wide “Y” shape).

- Why it works: Moving between W and Y targets multiple scapular movement patterns—retraction, upward rotation, and depression. This makes it excellent for improving shoulder mobility and posture.

- Muscles Worked: Rhomboids, lower traps, serratus anterior, rear delts.

- Trainer Tip: Keep your lower back against the wall to avoid compensation. Move slowly to maximize muscle activation.

2. Seated Back-to-Wall Slides

Instead of standing, you sit with your back fully against the wall and perform the slide motion.

- Why it works: Sitting removes lower-body compensation and forces better spinal alignment. It’s a great regression for beginners or people with poor mobility.

- Muscles Worked: Mid traps, rhomboids, external rotators.

- Trainer Tip: Keep your ribs tucked down and avoid arching your lower back. Imagine pressing your spine into the wall.

3. Mini-Band Wall Slides

Place a small resistance band around your wrists or forearms, then perform standard wall slides.

- Why it works: The band adds lateral resistance, forcing your serratus anterior and rotator cuff to engage more actively. This variation improves shoulder stability and scapular control.

- Muscles Worked: Serratus anterior, rotator cuff, traps.

- Trainer Tip: Apply gentle outward pressure on the band throughout the movement. Don’t let your hands collapse inward.

Who Should Do Scapular Wall Slides?

- Desk workers & students: Counters rounded shoulders and forward-head posture.

- Overhead-sport athletes: Swimmers, volleyball/tennis players, and throwers benefit from stronger scapular control.

- Weightlifters & CrossFitters: Improves mobility and stability for presses, jerks, and snatches.

- Rehab patients: Commonly included for impingement, scapular dyskinesis, and rotator-cuff weakness (as cleared by a clinician).

- Older adults: Low-impact and joint-friendly for maintaining posture and shoulder health.

If posture, shoulder pain, or overhead strength is an issue, wall slides are a smart addition.

When to Include Scapular Wall Slides in Your Routine

- Warm-up: 2–3 sets before pressing or pulling to prime scapular control.

- Daily posture breaks: Short sets during the workday to offset sitting.

- Rehab & physical therapy: Use per clinician guidance to reinforce proper scapular rhythm.

- Mobility for lifters: Integrate on technique days for overhead movements.

- Cool-down/active recovery: Light sets to groove healthy patterns post-training.

Consistency wins: Regular practice—gym or office—drives lasting posture and strength changes.

Research Insights

A 2016 clinical trial on individuals with scapular downward rotation showed that wall slides improved scapular alignment and significantly reduced shoulder pain after just four weeks.

Sports physical therapists also recommend scapular wall slides to retrain proper scapular rhythm, making them an evidence-based choice for posture and shoulder rehab. This recommendation is grounded in the understanding that when scapular stabilizers are weak, normal scapulohumeral movement is disrupted—interventions that restore dynamic scapular control are essential for efficient shoulder mechanics

FAQ

1. Are scapular wall slides good for shoulder pain?

Yes, studies show they reduce pain by restoring proper scapular mechanics.

2. How often should I do scapular wall slides?

3–4 times per week is ideal, especially before upper-body workouts.

3. Can beginners do scapular wall slides?

Absolutely. Start with seated or back-to-wall variations for easier alignment.

4. Do scapular wall slides build muscle?

They primarily improve stability and posture, but they also strengthen supporting muscles like the traps and serratus anterior.

5. Are wall slides safe for rotator cuff injuries?

Yes, if cleared by a doctor or physical therapist. They are often prescribed in rehab settings.

6. Do scapular wall slides help posture from sitting at a desk?

Yes—doing them daily helps reverse forward head and rounded shoulder posture from prolonged sitting.

Conclusion

Scapular wall slides are one of the simplest, most effective exercises for fixing posture and building shoulder strength. Whether you’re an athlete, office worker, or recovering from shoulder pain, this low-equipment drill trains the right muscles for healthy shoulder mechanics.

👉 Start adding 2–3 sets into your warm-up or daily routine. Over time, you’ll notice better posture, reduced pain, and stronger, more mobile shoulders.

References

- Kwon JW, Ha SM, Park DS, Jeon IC, Lee SY. (2016). The effects of scapular wall slide exercise on scapular alignment, pain, and pressure pain threshold in individuals with scapular downward rotation syndrome. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 28(7), 1988–1992.

- Ha SM, Kwon OY, Cynn HS, Lee WH, Kim SJ, Park KN. (2010). Effects of passive correction of scapular position on pain, proprioception, and range of motion in subjects with scapular downward rotation. Manual Therapy, 15(6), 553–559.

- Ha SM, Oh JS, Cynn HS, Kwon OY, Kim SH, Kim SJ, Park KN. (2014). Effects of scapular posterior tilt exercise on scapular alignment, scapular muscle activity, and pain in subjects with scapular downward rotation. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology, 24(4), 548–554.

- Ludewig PM, Reynolds JF. (2009). The role of scapular dysfunction in shoulder impingement syndrome: a clinical commentary. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 39(2), 90–104.