The Asian squat is a deep, flat-footed squat where your hips drop below your knees, heels remain on the ground, and your torso stays upright.

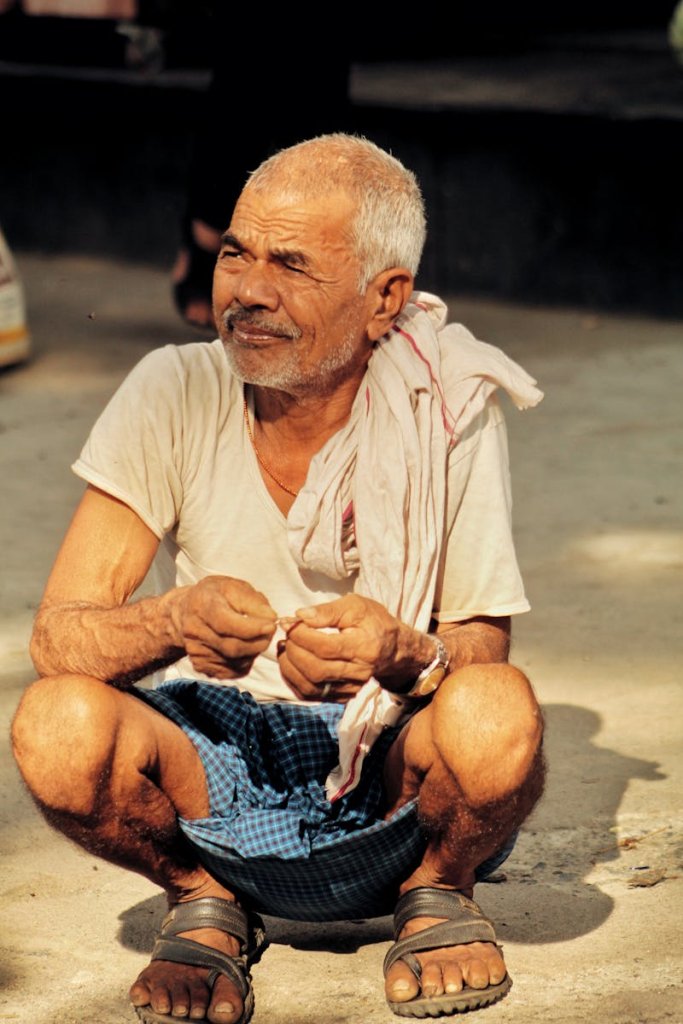

It’s a natural resting posture in many Asian cultures, often used for eating, cooking, socializing, or working close to the ground. Recently, it has become a global fitness trend because it challenges joint mobility, builds lower-body strength, and improves functional movement.

For many people—especially in Western, chair-based cultures—this position is surprisingly hard to maintain. Mastering it can unlock better posture, stronger legs, and pain-free daily movement.

What Exactly Is the Asian Squat?

The Asian squat is not just a gym exercise—it’s a functional, everyday posture that has been part of daily life in countries like China, Japan, Korea, Thailand, and Vietnam for centuries.

Key features of the Asian squat:

- Heels flat on the ground

- Hips below knee level

- Upright torso for balance

- Weight evenly distributed across both feet

- Chest open, not collapsed forward

In Asia, you might see people holding this position for minutes or even hours while chatting, preparing food, or waiting for a bus. In contrast, many people in Western countries struggle to hold it for more than a few seconds without falling backward.

Why Is the Asian Squat So Hyped in Fitness Circles?

There’s a reason mobility coaches, physiotherapists, and strength trainers love the Asian squat—it’s a quick diagnostic tool for ankle flexibility, hip mobility, and core stability.

Why fitness professionals recommend it:

- Mobility benchmark: It reveals restrictions in ankles, hips, and lower back.

- Full-body engagement: Requires multiple muscles to work together for balance and control.

- Functional relevance: Mimics natural human resting positions before chairs became common.

- Joint longevity: Keeps your hips, knees, and ankles moving through their full range.

Example:

Limited ankle dorsiflexion is well-documented to alter squat mechanics, often leading to increased dynamic knee valgus and difficulty keeping the heels down—key factors in inefficient or potentially harmful movement patterns (studies on ankle ROM and kinematic consequences of dorsiflexion restriction).

Benefits of the Asian Squat (Backed by Science)

1. Improved Mobility and Flexibility

- Stretches the calves, Achilles tendon, and hip flexors.

- Promotes ankle dorsiflexion, which is essential for proper walking, running, and jumping mechanics.

- Loosens tight hips from prolonged sitting.

Tip: If you feel your heels lifting, your ankle mobility needs attention.

(Dorsiflexion limits & compensation; knee valgus patterns with limited dorsiflexion.)

2) Lower-Body Strength & Control

The position engages:

- Quadriceps for knee extension

- Glutes for hip stability

- Hamstrings for balance

- Calves for ankle control

- Core muscles for upright posture

Example: Farmers in rural Asia often squat for hours while harvesting crops without back pain—proof that strong legs and hips support everyday labor.

(2024 squat biomechanics review.)

3) Joint Health & Posture

Deep, controlled ranges promote joint nourishment via movement and can counter chair-induced stiffness. Using the posture as a gentle “rest” position encourages a neutral spine rather than a slouched sit. (See the cultural overview on relaxed, sustained squatting.)

4) Pelvic Floor & Digestive Advantages

Squatting straightens the recto anal angle and can reduce straining during bowel movements, which helps explain why squat toilets remain common. Clinical work has shown faster, easier defecation and a more favorable angle in squatting versus sitting. (Sikirov 2003; Sakakibara 2010; DPMD outcomes (2019); 2025 scoping review.)

5) Posture and Back Health

Unlike slouching in a chair, the Asian squat encourages a neutral spine. This reduces strain on the lumbar region and helps prevent lower-back stiffness.

How to Perform the Asian Squat (Step-by-Step)

- Warm up (3–5 min): ankle rolls, calf stretch (knees bent & straight), hip flexor lunge, deep breathing.

- Set your stance: feet about shoulder-width, toes turned out 5–20°.

- Descend together: bend at hips and knees; keep chest tall and ribs stacked over pelvis.

- Keep heels down: if they lift, reduce depth or add a small heel wedge temporarily.

- Find balance: press knees slightly out; brace lightly through the core.

- Hold & breathe: start with 20–30 seconds; progress to 2–5 minutes as mobility improves.

Form Cues That Help

- “Tripod foot” (big toe, little toe, heel) stays grounded.

- Knees track over the middle of the foot; avoid collapsing inward.

- Keep eyes forward and spine long; don’t tuck the tail excessively.

Beginner-Friendly Modifications

- Heel support: place a rolled towel or small plate under heels to access depth while you build ankle ROM.

- Assisted squat: hold a doorframe or suspension strap for balance.

- Counterbalance (goblet): hold a light kettlebell/dumbbell at chest height to help you stay upright; this is well-regarded for learning clean squat patterns. (Goblet squat for beginners.)

- Partial range: practice “half squats” and sink a little deeper each week.

Why Some People Struggle (and How to Fix It)

- Limited ankle dorsiflexion: tight calves/Achilles shift you backward or onto toes. Target calf flexibility and ankle mobility drills. (Ankle DF limits & compensations.)

- Hip stiffness: long hours of chair-sitting shorten hip flexors and reduce deep flexion comfort; add 90/90 hip switches, lunges, and deep-supported holds.

- Proportions & levers: longer femurs make torso-upright balance harder—use a counterweight (goblet) and slightly wider stance.

- Core control: practice “brace & breathe” (360° expansion) to avoid collapsing forward.

How to Incorporate the Asian Squat Into Your Routine

- Micro-breaks at work: accumulate 3–5 minutes daily in 30–60s holds.

- Warm-up on leg day: 2–3 holds of 30–60s between mobility drills.

- Mobility circuits: ankle rocks → Asian squat hold → hip opener lunge (2–3 rounds).

- Everyday life: use it while scrolling, prepping food at a low surface, or tying shoes.

Safety Notes

- Discomfort (stretch/tension) is fine; sharp knee or ankle pain is not—modify or reduce depth.

- Keep knees tracking with the toes; avoid valgus collapse, especially if ankles are stiff. (Valgus & limited DF.)

- If you have recent lower-limb injuries or symptomatic osteoarthritis, get individualized guidance; occupational squatting for long durations has been associated with knee OA risk in some populations. (Squatting & knee OA risk in occupational settings; OA burden overview.)

Frequently Asked Questions

Is the Asian squat bad for your knees?

With aligned knees (tracking over toes) and controlled depth, it can build knee resilience. Problems usually appear when ankle mobility is restricted—leading to valgus or excessive forward knee travel. (Mechanics with limited DF.)

How long should I hold it?

Beginners: 20–30 seconds, 2–4 sets daily. Progress toward 2–5 minute relaxed holds over a few weeks. Use heel wedges or assistance as needed while you improve mobility.

What if my heels won’t stay down?

Use a small wedge temporarily and focus on ankle mobility: bent-knee calf stretches, wall ankle dorsiflexion rocks, and slow eccentrics. As dorsiflexion improves, remove the wedge. (DF & squat depth.)

Is this the same as a weightlifting “ass-to-grass” squat?

Similar depth, different intent. The Asian squat is a resting position; the Olympic squat is a loaded lift with performance and bar path considerations. See the 2024 biomechanical review for how depth affects muscle activation under load. (Squat depth & activation.)

Does squatting really help with digestion?

Evidence suggests squatting increases the recto anal angle and can reduce straining time versus sitting, which may ease bowel movements for some individuals. (Sikirov 2003; Sakakibara 2010.)

Conclusion

The Asian squat is more than a cultural habit—it’s a mobility benchmark, strength builder, and functional rest position. Whether you want healthier joints, better posture, or improved flexibility, adding just a few minutes of this movement into your day can make a big difference.

References (Selected)

- Macrum et al., 2012 – Ankle dorsiflexion limits & squat mechanics.

- Dill et al., 2014 – Altered knee/ankle kinematics with limited DF.

- Straub et al., 2024 – Biomechanical review of the squat.

- Sikirov, 2003 – Defecation position study; Sakakibara, 2010 – Rectoanal angle in squatting; Modi et al., 2019 – DPMD outcomes; Rahgoshay et al., 2025 – Toilet posture scoping review.

- Heidari, 2011 – Knee OA & occupational squatting; Lancet Rheumatology, 2023 – Global OA burden.

- SELF – Why the goblet squat helps beginners.